Two hundred and forty years ago this month in October 1780, Old Pauline Major John Andre was hung as a spy during the American War of Independence. At the time it was a major cause celebre on both sides of the Atlantic. Andre was eventually buried in Westminster Abbey in 1821 and the peach tree on which he was hanged was replanted in King George’s garden at Carlton House.

It is usually the case that when a Pauline’s school career is only mentioned in sources in terms of under which High Master they were at St Paul’s, nothing much is known except that he attended. Such is the case with Andre. Information about Andre builds from when aged 21 he was gazetted Lieutenant in September 1771. During the early days of the American Revolution, Andre was captured in 1775. A year later he was freed in a prisoner exchange. He was promoted to captain in 1777 and to major in 1780.

Andre was well known in colonial society, both in Philadelphia and New York, during those cities’ occupation by the British Army. He could draw, paint, and create silhouettes, as well as sing and write verse. He was fluent in French, German, and Italian.

During his time in Philadelphia, Andre occupied Benjamin Franklin’s house, from which it has been claimed that he removed several valuable items on the orders of Major-General Charles Grey when the British left Philadelphia. These included an oil portrait of Franklin by Benjamin Wilson. Grey’s descendants returned Franklin’s portrait to the United States in 1906, the bicentennial of Franklin’s birth. The painting now hangs in the White House.

At the time of his death Andre was Adjutant-General of the British Forces serving in America under Sir Henry Clinton. Benedict Arnold, the hero of the battles of Stillwater, which had led to the surrender of the British force under Burgoyne at Saratoga in 1777, was in command of the important fort of West Point (now the United States Military College) on the Hudson River. Arnold opened secret negotiations with Sir Henry Clinton for the surrender of West Point and other neighbouring forts to the British.

Major Andre was sent up the Hudson to conclude terms with Arnold. Having completed his mission, Andre was returning with plans of West Point and full details of the American forces in Arnold’s handwriting concealed in his stocking. He rode to the river bank, where he was to rendezvous with a man-of-war’s boat; the boat’s crew failed to meet him, and Andre attempted to make his way to New York through the American lines.

In the forest he was met by a patrol of three American militiamen. Thinking they were friendly, Andre declared himself a British officer. He was no longer in uniform.

When the compromising papers were found, his captors treated him as a spy rather than as a prisoner of war. He was tried in late September 1780 by a court-martial presided over by General Nathaniel Greene; the French General Lafayette was a member of the court.

Andre frankly disclosed all the facts. No witnesses were examined. Based on his confession, the court reported to George Washington that the prisoner ought to be considered a spy and be hanged. Washington, despite a letter from Andre requesting to be shot (a soldier’s death), ordered the hanging to take place. While a prisoner, Andre endeared himself to the American guards. Alexander Hamilton wrote of him: “Never perhaps did any man suffer death with more justice, or deserve it less.” The day before his hanging, Andre drew a likeness of himself with pen and ink, which is now owned by Yale. According to witnesses, he placed the noose around his own neck and his last words were reported to be, “I have nothing more to say, gentlemen, but this: you all bear witness that I meet my fate as a brave man.”

This notice of his execution appeared in the New London Gazette of 2 October 1780:

“This day at 12 o’clock the execution of Major Andre took place by hanging him by the neck. Perhaps no person, on like occasion, ever suffered the ignominious death that was more regretted by officers and soldiers of every rank in our army; nor did I ever see any person meet his fee with more fortitude and equal conduct. When he was ordered to mount the waggon under the gallows he replied, he was ready to die; but wished the mode to have been in a more eligible way, preferring to be shot.’ After he had opened his shirt-collar, fixed the rope, and tied the silk handkerchief over his eyes, he was asked by the officer commanding the troops if he wished to say anything. He replied, I have said all I had to before, and have only to request the gentlemen present to bear testimony that I met my death as a brave man.'”

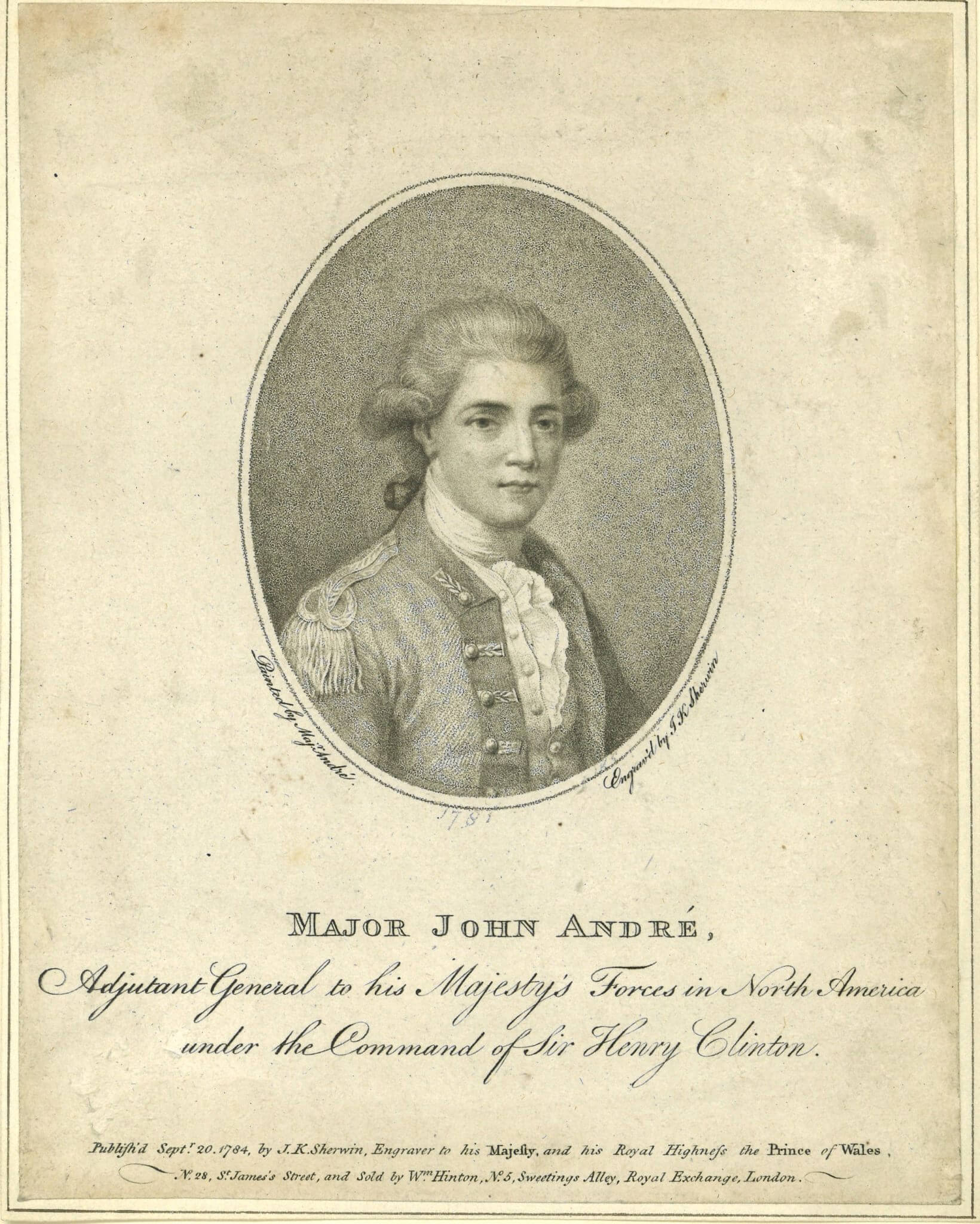

In 1891 an article appeared in The Pauline based on the research of Dr Collison Morley, who donated a portrait of Major Andre to St Paul’s School and exhibited the letter from Andre to George Washington requesting that he be shot as a soldier rather than being hanged as a spy in The Great Hall of the School.

Extract from The Pauline May 1891

MAJOR JOHN ANDRE

We have already had an opportunity of thanking Dr Collison Morley in the name of the School for the collection of portraits of eminent Paulines, which now hang in the Great Hall. Of all these portraits there are none to which a great interest attaches than to those of Major Andre.

Not the least valuable part of Dr Morley’s gift is the short summary of the principal events in the life of each person represented, which is in every case framed with the portrait. But in the case of Major Andre, Dr Morley, who is himself an old military man, has been at infinite pains to collect and verify the smallest detail of his tragic fate. Much of this information has not, we believe, hitherto appeared in print, and the details could naturally not receive full treatment within the limits of a small printed slip. But Dr Morley has been good enough to put all papers and documents that he had collected into our hands, and from them, with his permission, the following article is compiled.

The documents include a copy of the Regimental Records of the 54th (West Norfolk) Regiment, to which Andre belonged; a letter from the postmaster of Tappan, N.Y., where Andre was executed; a letter from Lord Wolseley, giving information in possession of the Horse Guards; and a letter from Mr J. Lewis Andre, of Horsham, containing details in possession of the family. We are fortunate in being able to give our readers the result of Dr Morley’s investigations, and the school owes him a great debt for the enthusiastic and almost patriotic labour that he has spent on his inquiry into the circumstances of the death of one whose name is not the least glorious in the long roll of Paulines who have served their country in Church and State.

John Lewis Andre was the son of a merchant carrying on business in Warnford Court. The family originally came from Geneva. John Andre was born in London in 1751, and entered St. Paul’s School under the high mastership of George Thicknesse. How long he remained in the school is uncertain, but he was sent to complete his education at Geneva, and subsequently entered his father’s counting-house. This, however, he soon left to enter the army, where his promotion was singularly rapid. He was gazetted Lieutenant in the 7th Foot, 24th September, 1771; promoted Captain 26th Foot, 18th January, 1777; removed Captain 54th Foot, 9th September, 1779; promoted Brig.-Major, 5th August, 1780.

At the time of his death he was Adjutant-General of the British Forces serving in America under Sir Henry Clinton. At that time Benedict Arnold, one of the most distinguished of the American generals and the hero of the battles of Stillwater, which had led to the surrender of the British force under Burgoyne at Saratoga on October 16th, 1777, was in command of the important fort of West Point on the Hudson River, now the site of the United States Military College. Arnold, for reasons which it is not necessary to go into, considered himself ill-used by the American Government, and in revenge, by an act of perfidy which has become proverbial, opened secret negotiations with Sir Henry Clinton for the surrender of West Point and other neighbouring forts to the British.

Major Andre was sent up the Hudson in the Vulture sloop of war to conclude terms with the traitor, and to offer him £10,000 and a Brigadier-Generalship as the price of his treason. He accomplished this difficult and dangerous mission successfully, completed the bargain with the traitor, and was returning with plans of West Point and full details of the American forces in Arnold’s handwriting concealed in his stocking. He rode to the river bank, where a man-of-war’s boat was to await him; but whether owing to a fog, as the records of his regiment state, or whether, according to the account current in America, a gun had been trained on the Vulture and she had been obliged to drop down stream, the boat’s crew failed to meet him, and Andre was obliged to attempt to make the best of his way to New York through the American lines.

In the forest he was met by a patrol of three American militiamen, named John Paulding, David Williams, and Isaac Varnort. Mistaking them for English he declared himself a British officer. On discovering his error he produced a pass with which Arnold had furnished him, but his captors declined to let him go, and conducted him to the American lines. Unfortunately Andre no longer wore the British uniform, which, while lying in concealment after his interview with Arnold, he had been persuaded to exchange for civilian costume.

When the compromising papers were found upon him, this fact decided his captors to try him as a spy rather than treat him as a prisoner of war. He was accordingly tried in the last days of September 1780, by a Court-martial of general officers, presided over by General Nathaniel Greene, the celebrated French General Lafayette being a member of the Court.

Andre, anxious to save his reputation from all suspicion of dishonour, at once frankly disclosed all the facts that bore against himself, remaining silent on every point that might compromise others. No witnesses were examined, but on the strength of his confession the Court reported to Washington that the prisoner ought to be considered a spy and accordingly to suffer death by hanging. Washington ordered the execution to take place the following afternoon; but in consequence of a flag of truce from the English, the execution was postponed.

Meanwhile Sir H. Clinton had sent General Robertson to urge to Washington everything that was in Andre’s favour, but in vain. Washington would only consent to spare Andre on condition of the surrender of Arnold, who by this time had fled to the British lines. Andre was accordingly sentenced to be hanged as a spy.

On receiving his sentence he wrote to Washington a dignified and pathetic letter asking that he might suffer a soldier’s death by being shot. This letter is appended to the portrait of Andre now in the Great Hall, where all can read it. The letter had a great effect on Washington, and he laid it before the court-martial. The members of the Court were unanimous in favour of granting Andre’s request, with the exception of General Greene, who wrote to Washington that the prisoner on his own confession was convicted of being a common spy; that the public safety called for a solemn and impressive example; that if Andre was shot instead of being hanged, public compassion would be awakened, and the belief would become general that in his case there were exculpatory circumstances entitling him to lenity beyond what he received ; and that there was no alternative between hanging him and setting him free. Greene, in writing this letter, is said to have felt the liveliest compassion for the prisoner, but his reasoning prevailed, and Washington with tears in his eyes signed the warrant for execution. The details of the execution are given in Dr Morley’s account.

The following notice of it appeared in the New London Gazette of October 2nd, 1780:

” This day at 12 o’clock the execution of Major Andre took place by hanging him by the neck. Perhaps no person, on like occasion, ever suffered the ignominious death that was more regretted by officers and soldiers of every rank in our army; nor did I ever see any person meet his fee with more fortitude and equal conduct. When he was ordered to mount the waggon under the gallows he replied, he was ready to die; but wished the mode to have been in a more eligible way, preferring to be shot.’ After he had opened his shirt-collar, fixed the rope, and tied the silk handkerchief over his eyes, he was asked by the officer commanding the troops if he wished to say anything. He replied, I have said all I had to before, and have only to request the gentlemen present to bear testimony that I met my death as a brave man.'”

The news of Andre’s death was received with great indignation in England. As a mark of the universal respect in which his memory was held, his brother was made a baronet. Forty years later, at the request of the Duke of York, Andre’s body was removed from its grave beneath the gallows and transported to England. On opening the grave, a few locks of his hair were found and sent to his sisters. The roots of a peach-tree had pierced the coffin and twisted themselves round his skull. In 1868 an old American lady was still alive who remembered as a girl having given Andre a peach off that very tree. The peach tree itself was taken up and replanted in the King’s garden behind Carlton House.

The body was brought to London and re-buried with great solemnity in Westminster Abbey, the funeral service being conducted by Dean Ireland. A memorial tablet by Van Gelder was fixed in the neighbouring wall, and is no doubt familiar to many of us. On the monument is a bas-relief representing Washington receiving the letter either of Andre or of Clinton. The head of one or other of the figures has frequently been carried off. Dean Stanley incredibly suggests by the pranks of the Westminster boys. Charles Lamb used to twit Southey, who was at school at Westminster and in his youth an ardent republican, with being concerned in the outrage.

Nor did the scene of the execution remain unmarked by a monument. It is not indeed true, as is generally supposed, that the officers of the American Army testified to their admiration of Andre’s character in this way. But in 1879, Mr Cyrus W. Field, of New York, at the suggestion of Dean Stanley, who had in his visit to America identified the place of Andre’s execution, erected a monument to mark the historic spot. This monument has a strange history. On the night of February 22nd, 1882, an attempt was made to blow it up with dynamite. Another and successful attempt was made on the night of March 19th of the same year. In 1884, Mr Field visited the place in company with Archdeacon Farrar, and subsequently had the monument set up again. On November 8th, 1884, it was again blown up, and it now lies with the base shattered but the shaft practically undamaged. The perpetrators of the outrage were never discovered, but it is supposed that they were Fenians who came out from New York for the purpose, animated with a dislike for everything English.

The inscription which Dean Stanley wrote for the monument is as follows: “Here died, October 2nd, 1780, Major John Andre, of the British Army, who, entering the American lines on a secret mission to Benedict Arnold for the surrender of West Point, was taken prisoner, tried, and condemned as a spy. His death, though according to the stern code of war, moved even his enemies to pity, and both armies mourned the fate of one so young and so brave.

In 1821 his remains were removed to Westminster Abbey. A hundred years after the execution this stone is placed above the spot where he lay, by a citizen of the United States against whom he fought, not to perpetuate the record of strife, but in token of those better feelings which have since united two nations one in race, in language, and in religion, with the hope that this friendly union will never be broken.”

Andre, besides being a soldier whose professional skill is sufficiently proved by the high rank that at the time of his death at the age of twenty-nine he had attained in the British Army, was also possessed of considerable literary and artistic ability. His satirical poem “The Cowchase” gave great offence at the time in America. He was a clever miniature painter, and his portrait at the age of eighteen, painted by himself, is the original of one of the prints now in the possession of the school. The pen-and-ink sketch of himself, done in York Island, which is also reproduced on our walls, 18 from an original now in the possession of J. Lewis Andre, Esq., F.S.A. of Sarcelles, Horsham. His portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, which represents him in a red coat and yellow vest trimmed with fur, was in the exhibition of the National Portrait Gallery in 1867, and is the property of Sir Hugh Shafto Adair, of Flixton Hall, Suffolk.

At a time when all the country has been stirred by the gallant conduct of a young officer in whom St Paul’s may claim an indirect interest, and who, at the same age as Andre, has, fortunately with a more happy result, proved that the old traditions of courage and devotion are still alive in the British Army, it is hoped that this account of one whose name is scarcely less widely known than that of Marlborough himself, and whose reputation is as stainless as that of our other great military hero must be acknowledged to be the reverse, may not be without interest to a school which year by year sends out more of its members to serve their country in the army, if not to rival the military prowess of Marlborough, yet all of them to show the indomitable courage and chivalrous self-devotion of Andre.