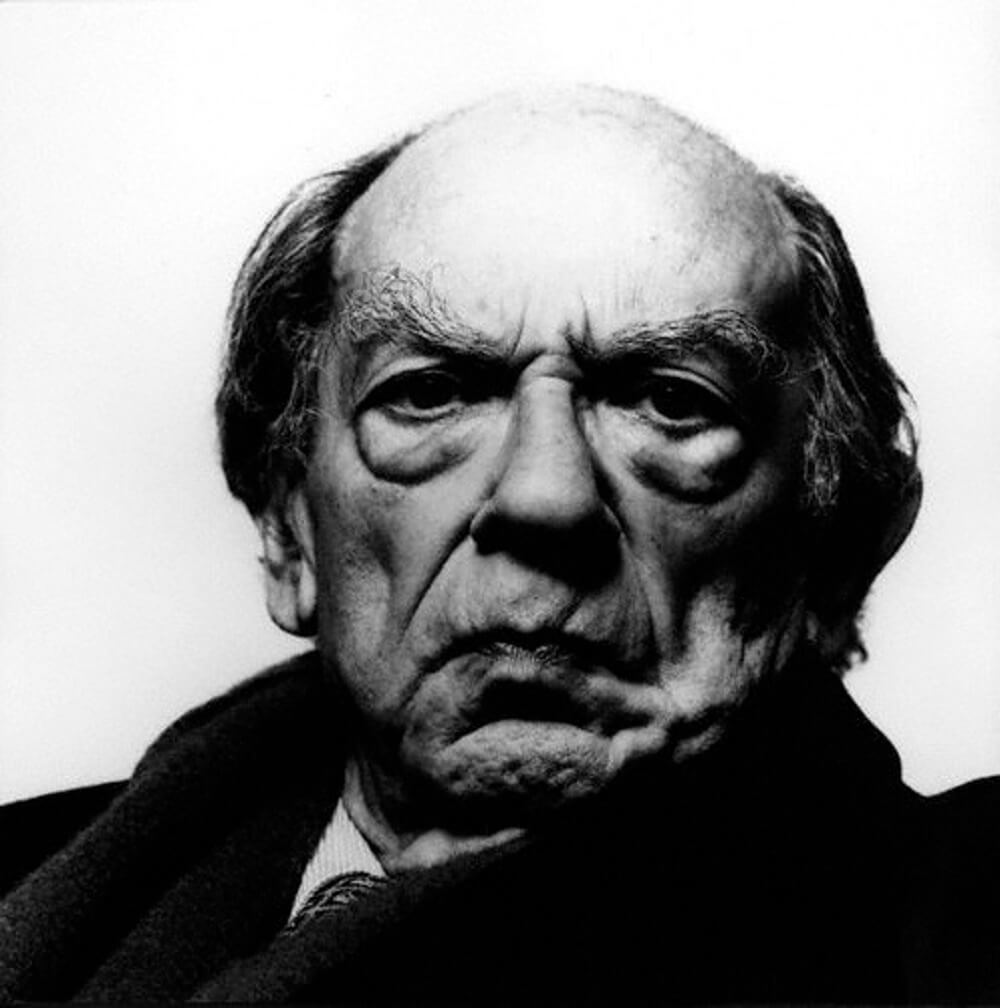

Sir Isaiah Berlin OM, CBE, FBA

Born in Riga in 1909, Berlin moved to Russia, at the age of six, where he witnessed the revolutions of 1917. In 1921 his family escaped to the UK. At the time Isaiah spoke 40 words of English. Plainly a fast learner he entered St Paul’s as a scholar in 1922.

Whenever he was described as an English philosopher, Berlin always insisted that he was not an English philosopher, but would forever be a Russian Jew: ‘I am a Russian Jew from Riga, and all my years in England cannot change this. I love England, I have been well treated here, and I cherish many things about English life, but I am a Russian Jew; that is how I was born and that is who I will be to the end of my life’.

He also described himself as a ‘natural assimilator’ and that he fitted well in England due to being unimaginative. During his final years at School he would lunch at The Dove with Pauline friends and discuss ‘Eliot and Ezra, bitter and Burton, Cocteau and Cambridge.’ Throughout his life Berlin was a great talker seemingly preferring it to writing with Maurice Bowra commenting, ‘he is like Our Lord and Socrates, he does not publish much.’ And on the award of his knighthood in 1957 Frederic Warburg suggested it should be for ‘services to conversation.’

Rejected by Balliol (the equivalent of a record company turning down The Beatles), Berlin took firsts in classical Greats and the new course of PPE at Corpus Christi. In 1932, at the age of twenty-three, Berlin was elected to a fellowship at All Souls. He was the first unconverted Jew to be a fellow there.

Berlin was to remain at Oxford for the rest of his life, apart from a period working for British Information Services in New York from 1940 to 1942, and for the British embassies in Washington and Moscow from then until 1946. Before World War II he taught philosophy but from 1950 he concentrated on the history of ideas succeeding OP GDH Cole* (1902-08) as Chichele professor of social and political theory in 1957. His opening lecture, Two Concepts of Liberty (often considered his most important work) explored how ideas of freedom could transpose into tyranny.

Berlin’s most famous essay is however The Hedgehog and the Fox. A title referring to a fragment of the ancient Greek poet Archilochus of which, Berlin once said “I never meant it very seriously. I meant it as a kind of enjoyable intellectual game, but it was taken seriously.” Berlin expands upon this idea to divide writers and thinkers into two categories: hedgehogs, who view the world through the lens of a single defining idea such as Plato and foxes, who draw on a wide variety of experiences and for whom the world cannot be boiled down to a single idea such as Shakespeare.

A lifelong Zionist, he resigned from the OPC when it became known that St Paul’s had a quota for non-Christian boys. He rejoined when the quota was abolished. There is the Isaiah Berlin Society at St Paul’s. The society invites academics to share their research into the answers to life’s great concerns and to respond to pupils’ questions. It has in recent years hosted: A.C. Grayling, Brad Hooker, Jonathan Dancy, John Cottingham, Tim Crane, Arif Ahmed, Hugh Mellor and David Papineau.

Berlin died in Oxford in 1997, aged 88. He dictated a plea for reconciliation between Israelis and Palestinians on his deathbed; this was published in Israel on the day of his burial. Meanwhile the front page of The New York Times concluded: “His was an exuberant life crowded with joys – the joy of thought, the joy of music, the joy of good friends. The theme that runs throughout his work is his concern with liberty and the dignity of human beings. Sir Isaiah radiated well-being”. This shines through in an interview with Michael Ignatieff about Berlin’s life shown at his request after he had died.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDAGngAc9_M

* When Who’s Who first invited Cole to send in an entry, he showed a draft to his wife. Under Recreation, he had entered ‘to diaphtheirein tous neous’ (corrupting the young men). When Margaret suggested this was unwise, he said in an astonished voice ‘but of course I meant politically’.

Sue Lawley hosted Isaiah Berlin on Desert Island Discs in 1997. He clearly preferred operatic and classical to more contemporary music. His book choice again reminds us that he was a Russian.

Modest Mussorgsky – Clock Scene (from Boris Godunov)

Giuseppe Verdi – Ah, fors’ è lui (from La Traviata)

Johann Sebastian Bach – Violin Concerto No. 2 in E major – 2nd movement

Ludwig van Beethoven – Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111

Gioachino Rossini – The Italian Girl in Algiers Overture

Ludwig van Beethoven – String Quartet No.14 in C sharp minor, Op. 131

Franz Schubert – Piano Sonata No. 21 in B flat major, D960 -2nd movement

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – L’ho perduta (from The Marriage of Figaro)

Book

Works, prose and verse – Aleksandr Pushkin

Luxury

Large armchair stuffed with cushions

Click here to read Orlando Gibbs’ (2008-2013) article on Berlin from the Spring/Summer 2020 edition of Atrium.

Sir Isaiah Berlin OM CBE FBA

(1909-1997)

I don’t mind death. I’m not afraid of it. I’m afraid of dying for it could be painful. But I find death a nuisance; I object to it. I’d rather it didn’t happen . . . I’m terribly curious. I’d like to live forever.

Sir Isaiah Berlin, the philosopher and historian of ideas, and undoubtedly one of St. Paul’s School’s most famous alumni, died, aged 88, on 12th November 1997.

He was born in Riga, the capital of Latvia, on 6th June 1909 to Jewish parents. In 1917 his family moved to St. Petersburg, where, as a boy, Berlin witnessed the Social-Democratic and Bolshevik Revolutions. He attributed his life-long loathing of violence to what he saw during the course of 1917. Four years later, the Berlins moved to London.

In his last interview, Berlin claimed he was ‘a natural assimilator’, and in London he quickly added English traits to a melting-pot that already contained Latvian, Jewish, Russian, and German ones. When he was at prep school, he planned to continue his education at Westminster. One of his teachers, however, told him that he might not “be comfortable” at Westminster with a name like Isaiah. Instead he came to St. Paul’s. Recalling his Pauline days in an interview, Berlin said, “I never was at the head of a single class. I was fourth, fifth, seventh or eighth. But this didn’t bother me. Once, when I tried very, very hard, in my last year of St. Paul’s, I was second.”

As befitted his peripatetic childhood, Berlin studied languages: German, Latin, Greek, and English. His German was not first-class: his school reports show that he started with `obvious aptitude for this language'” but descended into being `moderate: he has not made much progress’. His Latin and Greek were better, with reports ranging from ‘excellent’ to `disappointingly mediocre’. It was in English, however, that Berlin excelled. His writing was declared to be ‘as attractive, and as effective, as anything I have had from a pupil’. Indeed foreshadowing praise that would follow Berlin throughout his career, his English master wrote that, ‘He has remarkable originality of thought and power of expression’.

At Apposition in 1928, he was awarded the Chancellor’s Prize and Medal for an English essay and the Butterworth Prize for English Literature. Instead of the modern system of declamations, Apposition in Berlin’s time included a play performed in Greek by the pupils. Berlin played the role of Meton in Aristophanes’ The Birds. Meton is described as a `venerable old gentleman’ but, unlike Berlin in his old age, he ‘is, however, quite unintelligible, and is promptly sent about his business’.

Despite having lived in England for only five years, Berlin tried for but did not receive an award to Balliol College, Oxford. The High Master at the time, A E Hillard, wrote in his report that “it would have been an unusual success if he had got a Balliol scholarship or exhibition”. A year later however, the new High Master, John Bell, was able to write that “he has justified himself by gaining a scholarship to Corpus [Christi]” and that “he has the prospect of a brilliant career at Oxford”.

Bell, when making this comment, naturally assumed Berlin’s Oxford career would end as a graduate, since he had no idea what to pursue as a career. Bell was correct but to a greater extent than he had expected. Berlin did gain first-class degrees in Greats and PPE, and, after considering journalism, law, and his father’s timber business, he was appointed a Lecturer in Philosophy at New College, thereby beginning a truly glittering academic career. He won a Prize Fellowship to All Souls in 1932 and was made a Fellow of New College in 1938. In 1957 he was chosen to be the Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at Oxford and, in 1966, became the founding President of Wolfson College. In addition to Oxford, he held visiting professorships at several other prestigious universities. He was made a Fellow of the British Academy in 1957, becoming its Vice-President in 1959 and its President in 1974.

Berlin used to claim that his reputation was based on a `systematic overestimation’ of his abilities. It is true that he never produced a single magnum opus, claiming that “I have never had it in me to do a great masterpiece on some big subject”. Moreover, he published less than some more verbose academics. Indeed his friend Maurice Bowra claimed that “like Our Lord and Socrates, he does not publish much, but thinks and says a great deal and has had an enormous influence”. This quotation notwithstanding, Berlin did publish many articles, often in fairly obscure journals, that have been collected by Henry Hardy into six volumes, as well four main books: Karl Marx, Four Essays on Liberty, Vico and Herder, and The Magus of the North. It is as a talker, not a writer, however, that Berlin will probably be most remembered. He was famously spell-binding in lectures and conversations and spoke very quickly, using long sentences, full of sub-clauses and digressions that nevertheless remained grammatically perfect. Indeed, much of the attraction of his essays stems from the energy and passion conveyed in what are essentially written lectures, a writing style once described as ‘Gibbon on a motorbike’.

Berlin once claimed the main theme of his work was ‘the distrust of all claims to the possession of incorrigible knowledge about issues of fact or principle in any sphere of human behaviour'”. This over-arching goal manifested itself in his three most important contributions to philosophy: his attack on historical inevitability, his analysis of liberty, and his defence of pluralism. In a century where Marxism, oppression, and totalitarianism threatened to dominate the globe, Berlin’s contribution was, as William Waldegrave put it in his obituary in the Evening Standard, “to man the intellectual barricades”. Berlin refused to dismiss ideas such as Marxism simply as twaddle or to misrepresent them and then attack the resultant caricature; rather, he called Marx “a genius”, represented his ideas faithfully, and then refuted them in Karl Marx: His Life and Environment, written at All Souls and published in 1939. Berlin recognised the importance of his role:

When ideas are neglected by those who ought to attend to them — that is to say, those who have been trained to think critically about ideas — they often acquire an unchecked momentum and an irresistible power over multitudes of men that may grow too violent to be affected by rational criticism . . . Over a hundred years ago, the German poet Heine warned the French not to underestimate the power of ideas: philosophical concepts nurtured in the stillness of a professor’s study could destroy a civilisation . . . If professors can truly wield this fatal power, may it not be that only other professors, or, at least other thinkers (and not governments or congressional committees) can alone disarm them? Our philosophers seem oddly unaware of these devastating effects of their activities.

His analysis of liberty was most famously and effectively stated in his inaugural lecture as the Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory, entitled Two Concepts of Liberty. At the time, the lecture was claimed to be ‘a classic restatement of English liberalism’. Berlin explained that there was ‘negative’ liberty and `positive’ liberty. Negative liberty is the principle of laissez-faire — an individual can do as he or she pleases without the state interfering. Proponents of positive liberty assert that negative liberty only gives freedom in theory but not in practice. For example, in a laissez-faire society, the poor have the freedom in theory to take luxurious holidays; in practice, they may as well be shackled at home. Positive liberty, therefore, proclaims the principle that the state should interfere in society — with, for example, redistributive taxation — to ensure freedom in practice. Berlin came down on the side of negative liberty because positive liberty is so open to abuse by those in power. The decisions as to where laissez-faire should be tamed and where it should be left wild come down to arbitrary distinctions drawn by a state, which is often self-appointed and illegitimate, and even when not, can be a tyrannical majority. Granting positive liberty requires a decision taken by the state as to what sort of society it wishes to create. This creation is then imposed upon all uniformly, restricting the freedom of dissenters. Hence, positive liberty restricts the freedom of many to give some people ‘real’ freedom to achieve certain arbitrary, and hence often unwanted, goals; negative liberty gives everyone freedom, although some are unable to capitalise upon it.

Logically commensurate with a support of negative liberty is a defence of pluralism. His most memorable chapter in this defence is his essay The Hedgehog and the Fox, which was a wide-ranging study that began with an examination of Tolstoy’s theory’of history. The title of the essay came from the Greek poet Archilochus who explained that `the fox knows many little things, but hedgehog knows one big thing’. What Berlin found was that often hedgehogs were deadly because their one idea precluded others — they believed they could create a utopia. Berlin argues that `utopias have their value — nothing so wonderfully expands the imaginative horizons of human potentialities — but as guides to conduct they can prove literally fatal’. Utopias are neat, and they cannot be overlaid upon jagged reality, unless that reality is smoothed, a feat many — including Hitler, Mao Tse Tung, Stalin, and Pol Pot have attempted this century with truly abominable results:

The notion of the perfect whole, the ultimate solution, in which all good things coexist, seems to me to be not merely unattainable . . . but conceptually incoherent. We are doomed to choose, and every choice may entail an inseparable loss. Happy are those who live under a discipline that they accept without question . . . or those who have arrived at clear and unshakeable convictions about what to do and what to be that brook no possible doubt . . . Those who rest on such comfortable beds of dogma are victims of forms of self-induced myopia, blinkers that may make for contentment, but not for understanding what it is to be human.

What Berlin recognised is that there are six universal values: freedom, justice, equality, tolerance, compassion, and loyalty. These values, however, often conflict with one another. For example, one cannot have total liberty and total equality: with total liberty, inequalities can never be resolved and with total equality, liberty must be sacrificed to equality’s continuance. Hence, given that these values cannot co-exist totally peacefully, individuals must make choices, and these choices must be respected. Perfection may not be achieved, but a balance must be struck. This leads to pluralism.

It was these three contributions that endeared Berlin to so many, particularly in Britain, America, and Israel. He received twenty-three honorary doctorates, amongst others from Oxford, London, Harvard, Yale, Jerusalem, and Tel Aviv. He won the Jerusalem Prize for services to freedom, the Erasmus Prize for the history of ideas, and the Agnelli Ethics Prize. He was also highly revered by the English Establishment, with the CBE awarded in 1946 and a knighthood in 1957. Harold Macmillan, in reference to Berlin’s famed skills as a conversationalist and raconteur, wrote to the Queen that the knighthood should be given `for talking’. Indeed it is said that when Berlin went to receive his CBE, he interpreted George VI’s “a pleasure to meet you” as an invitation to conversation, and was promptly told by an equerry to “bend your neck and stop talking”. His greatest accolade from the Establishment came in 1971 when he was awarded the Order of Merit, held by only twenty-four people at any time.

One must wonder how a consciously Jewish, consciously Russian immigrant achieved such venerated status within the English Establishment. The answer has to be that Sir Isaiah Berlin was probably the person most responsible for protecting English values this century. He argued against over-arching ideologies, he argued against oppression in the name of freedom, and he argued against the inevitability of history. He refused to allow the complexity of reality to be subsumed by utopian theory, and in so doing, he protected liberalism, tolerance, and individual choice. Sir Isaiah Berlin manned the intellectual barricades and helped ensure that the open society triumphed and not its enemies.

He can always be relied upon to have ideas of his own, to express them well, and to make his essay interesting.

English Report, Summer Term 1926

Michael Birshan

Main photograph by Richard Avedon, 1993.